Nowhere Boy is inspired by the true story of Albert Jonnart, a Belgian lawyer, who hid Ralph Mayer, a Jewish teenage refugee in his house. I first heard of Albert’s story when I saw a sign at the end of my block, Avenue Albert Jonnart, which was named after him. It wasn’t clear to me whether Ralph survived the war but the story touched me deeply.

Jonnart came from a distinguished Belgian French family. After studying law, he served on the Court of Appeals in the Belgian Congo and fought in the First World War, before settling into public life as a lawyer for his commune or township. When the Second World War started, he joined the resistance, helping forge false identity papers, ration stamps, and documents to keep Belgians from being sent to work in Germany.

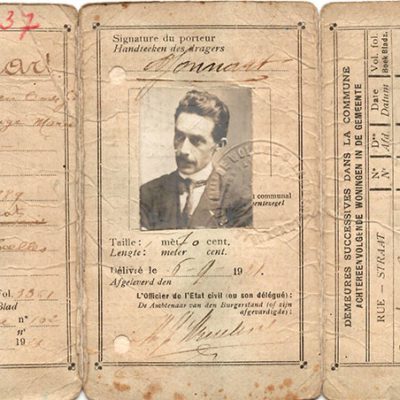

- Jonnart the student.

- Jonnart the soldier during the First World War.

- Jonnart the lawyer on his Belgian identity card.

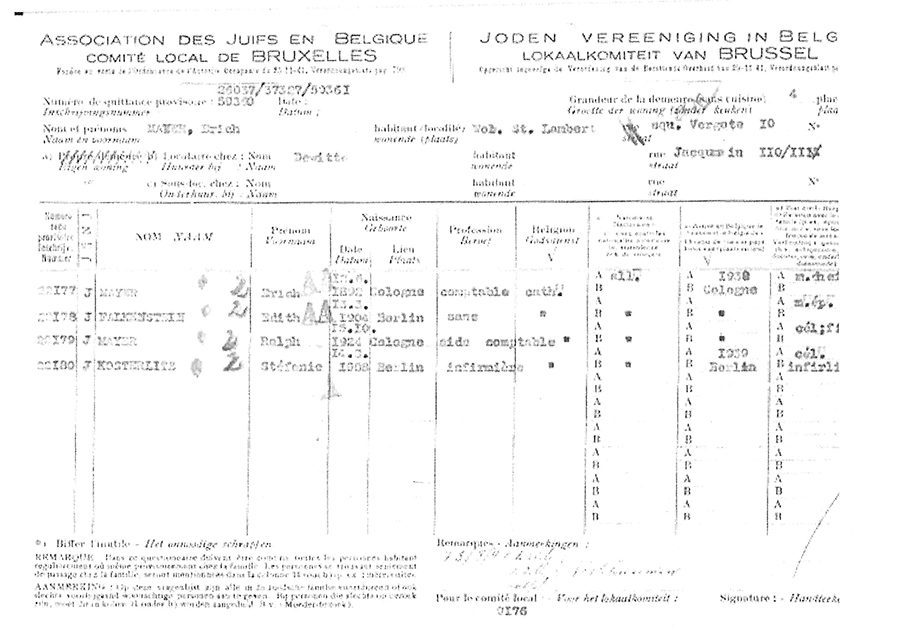

Ralph’s father, Erich Mayer, was a client of Albert Jonnart’s. Erich and his wife Edith Folkenstein had fled Germany after Hitler’s rise in the 1930s along with their son, Ralph. After Hitler invaded Belgium in 1940, Eric Mayer approached Albert to ask him to hide his son if the situation for Jews worsened. The Germans forced all Jews to register.

In August 1942, seventeen-year-old Ralph began to live secretly in an upper bedroom of the Jonnart family house. Albert was not the only courageous member of his family. His wife, Simone Deploige, agreed to shelter the boy and their three children kept the dangerous secret as well. His son, Pierre, who had been a high school classmate of Ralph’s at College Saint-Michel, brought Ralph books and assignments so he could keep up with his studies.

- Original document registering the Mayer family as German-born Jews in Brussels, Belgium.

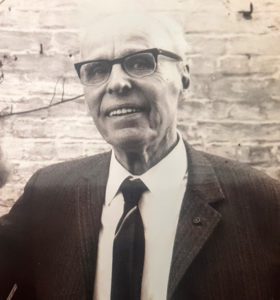

- Albert Jonnart and his wife Simone DePloige.

Ralph’s parents, Erich and Edith, moved into a house one block over on Rue Vergote where they lived openly with other Jews. At night, Ralph would sneak out to visit them. But a neighbor who was collaborating with the Nazis spotted the boy coming and going from Jonnart’s house and informed the Gestapo. At 5 a.m., on July 13, 1943, the Gestapo pounded on Jonnart’s door.

Albert sent his son Pierre upstairs to warn Ralph. In keeping with their emergency plan, Ralph climbed onto the neighboring roofs before scrambling down to a garden and making his escape. However, the Gestapo found the bed still warm with no body to account for it. They arrested Albert Jonnart and sent him to prison. They also raided the house where Ralph’s parents and the other Jewish families were living.

Pierre went to Jacques Breuer, the father of a friend of his from the Belgian boy scouts, who lived nearby and asked him to help Ralph. Jacques worked as a curator at the Museum Cinquaintenaire and he hid the boy among the antiquities, bringing him food and looking after him, until the Allies liberated Belgium from Nazi rule in September 1944.

Jacques Breuer, the museum curator, who hid Ralph until the end of the war in the Cinqauntenaire Museum where he worked.

Ralph survived the war but his parents did not. The Nazis sent Erich Mayer and Edith Falkenstein to Auschwitz, where they were murdered along with over a million others. The Nazis killed an estimated six million Jews during the Second World War as well as countless other “undesirables,” including the physically or mentally handicapped, Romani, gays, Slavs, political resistors, and others. The Nazis killed 25,000 Belgian Jews, nearly half of the country’s Jewish population.

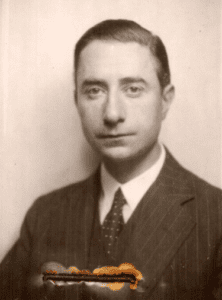

Above, the last known photos of Ralph’s parents–Erich Mayer and Edith Falkenstein. Below, Auschwitz, where the Nazis murdered them—and a million others.

Albert Jonnart continued his resistance work in prison, giving his fellow inmates legal advice. In a series of letters to his family, he maintained hope and his focus on his work, his Christian faith, and his duty to do the right thing. He was transferred to a work camp and tasked with helping build the Atlantic Wall, the fortifications meant to stop an Allied invasion of France. He died of overwork and malnutrition on March 15, 1944 at the age of 54. Three months later, D-Day and the Allied liberation of the continent began. Albert’s son, Pierre, joined the resistance and aided American troops during the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last offensive.

After the war, Ralph Mayer found Simone Deploige and, in an emotional reunion, thanked her for her husband’s sacrifice. He also kept in touch with the Breuer family, expressing his gratitude. Ralph married and lived in Brussels until his death in 1998. Every year on the anniversary of Albert Jonnart’s death, he sent Simone a bouquet.

A photo of the post-war reunion of Ralph Mayer and the surviving Jonnart and Breuer families. Ralph Mayer is second from the right. To his right is Jacques Breuer. Simone DePloige is second from the left. Pierre Jonnart is fifth from the left wearing glasses.

Pierre’s daughter, Bénédicte, grew up in the same house where her grandfather was arrested and heard the story from her grandmother Simone, who lived with her. Several years ago, Bénédicte learned about the Righteous Among Nations, a special designation from the State of Israel honoring non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. She became her family’s unofficial historian, assembling records and documents. In 2013, as a result of her efforts, the State of Israel designated both Albert and Simone “Righteous Among Nations.” Their names appear on a wall in the Garden of the Righteous in Jerusalem.

Bénédicte Jonnart pointing to her grandparents’ names on the Wall of the Righteous in Jerusalem, 2016.

For more information on Holocaust history and remembrance efforts, be sure to check out Yad Vashem.